On 24 February 2022, Russia launched an unprovoked full-scale attack on Ukraine aiming to decapitate its government and install a pro-Russian regime to achieve Putin’s revanchist vision of restoring the glory of the Russian empires.[1] Since then, numerous attempts have been made to make sense of the dramatic events in Ukraine that the world witnesses in real time. This feature brings together the voices of three Ukrainian scholars that explore various cultural processes as triggered, or re-triggered, in Ukrainian society by Russia’s escalated aggression. These are personal reflections on the state of cultural heritage in Ukraine as the war continues to unfold, brought together by Ukrainian Courtauld-based researcher Katia Denysova with an accompanying introduction that contextualises the historical roots of current events and the urgency of what is at stake in Ukraine today. The commissioned authors respond to some of the most debated concerns with academically informed discussions, envisioning the future of Ukrainian culture while also exploring the legacy of historiographical myths and the role that they continue to play in contemporary Ukrainian society.

Introduction

As I write this introduction, more than six months have passed since the first missiles interrupted the tranquillity of the winter morning all over Ukraine, forever shattering our perception of the world. Russia’s current invasion is not merely a manifestation of the Russian leadership’s opposition to Ukraine’s political trajectory and the perceived military threat that it poses. Rather, it is another chapter in the centuries-long saga of Russia’s attempts to deny Ukraine its independence, resting on the deep-seated belief that Ukraine is not a real country and Ukrainians are not a real nation. The war presents a very real danger to the physical survival of Ukraine’s rich cultural heritage, with almost all the country’s major cities suffering regular shelling. According to UNESCO, 183 cultural sites have been partially or totally destroyed in Ukraine since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale war.[2] The estimate of Ukraine’s Ministry of Culture is higher – 434 cultural heritage sites have been damaged or ruined in the last months.[3] Legal scholars are working to assess whether such actions constitute genocide, with many experts suggesting that the destroyed museums, monuments and religious sites are not casualties of war – their annihilation is an integral part of Russia’s targeted attempt to erase Ukrainian national identity.

Putin’s vision of history is based on an anachronistic combination of imperial tropes that intertwines the legacies of both the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. There are two notions that he appears to fixate on. First, the seventeenth-century myth, ironically created by monks from the Kyiv Cave Monastery, that presented Kyiv as the first capital of the Russian tsardom and the birthplace of the country’s Orthodoxy.[4] Second, the idea that Lenin artificially created Ukraine with the establishment of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1921.[5] Putin also subscribes to the Soviet-era narrative of ‘brotherly nations’, which gave Russian culture primacy over those of other constituent republics. Cherry-picking the historical events that best fit his agenda, Putin disregards centuries of complex historical context. The fight that Ukrainians are leading is, therefore, of a conceptual, or even existential, nature; at stake is the legitimacy of our existence as a nation.

Geopolitically, Ukraine has always been at the crossroads between west and east, a borderland separating the worlds of the Greek Byzantine and western cultures. For most of its history, the territory of present-day Ukraine was under foreign rule and Ukrainians were not known by their current name until the late nineteenth century. In modern historiography, Ukraine has been assigned to the camp of ‘non-historical’ nations, implying that it lacks continuity or historical legitimacy mainly due to the loss of state institutions and the absence of a traditional representative class.[6] Yet between the thirteenth and eighteenth centuries, there were periods of semi-independence that were crucial for the formation and preservation of a distinct Ukrainian identity. Its seeds were cultivated by Ukrainian writers of the early and mid-nineteenth century who started to give expression to national aspirations.[7] The project of Ukrainian nation-building commenced with an ethnic-linguistic community that developed into a cultural elite, which led to a political claim. The process culminated in the establishment of the short-lived Ukrainian People’s Republic (1917-1920) that lost to the Bolsheviks in the Ukrainian War of Independence, with the subsequent integration of the majority of Ukrainian lands into the USSR.[8]

Such a historical background gave rise to a vibrant amalgamation of influences, a blending of Polish, Russian, Austro-Hungarian, and Jewish elements that created a distinctly Ukrainian cultural profile. Further, the Soviet nationalities policy of the 1920s, known as korenizatsiia (indigenisation), provided Ukrainian culture with a framework to overcome its epigonism and regionalism. In theory, korenizatsiia was a strategy aimed at disarming local nationalisms by granting the constituent republics the chance to form national territories, staffed by home-grown elites that used their national language and promoted their local culture and identity.[9] In practice, the policy’s Ukrainian version, known as ukrainisatsiia (Ukrainisation), allowed local intellectuals to create a self-sufficient culture that was both Soviet and Ukrainian. The potency of this new Soviet-Ukrainian culture was conditioned by the energy and national drive of the local intelligentsia. Although temporary and completely reversed by Stalin in the 1930s, ukrainisatsiia stimulated Ukraine’s cultural breakaway from the provincialism inflicted by centuries of imperial rule.

The above complexities fail to register with Putin. But such a stance has been echoed, even if unwittingly, in the writings of some contemporary scholars. Boris Groys, for example, has maintained that citizens of the former Soviet Union came ‘from nowhere, from the degree zero at the end of every possible history’.[10] Hence, with the fall of communism, the post-communist societies had to travel backwards from the point where the historical past had been rejected and any kind of distinct cultural identity expunged. From this argument proceeds Groys’s claim that the present-day Russians, Ukrainians, and other nations of the former USSR, could not rediscover or redefine their alleged cultural identity, as required by postmodern cultural diversity, since it was ‘completely erased by the universalist Soviet social experiment’.[11] Ukrainians disagree. For while such a view can be entertained in theory, the Soviet Union in reality did not exist long enough for previous historical, and national, narratives and cultural distinctions to be completely obliterated.[12]

The Ukrainian-born USA-based historian Serhii Plokhy posits that one of the main characteristics of the history of Ukraine is the ability of its society to cross inner and outer frontiers and negotiate different identities created by them.[13] The history of Ukraine has never been homogenous, nor has its culture; consequently, Ukrainian society should continue to embrace and celebrate the resulting pluralism and multifacetedness. But this is not an easy task to carry out when the nation’s existence is threatened both physically and conceptually. Unlike Russian society, however, which fails to redeem itself for its imperialistic past and looks backwards in its attempt to rewrite history through aggression, the Ukrainian perspective looks forward, desiring to leave behind the ghosts of the past through the constructive reconstitution of its culture and identity. Three texts that follow passionately yet rigorously engage with the discourses of de-colonisation, de-communisation and de-russification in Ukraine. Svitlana Biedarieva’s essay outlines the responses of Ukrainian artists to the war, while also taking steps to critically reflect on the application of the anti-colonial, decolonial and postcolonial theories to Ukrainian contemporary art and reality. The interview with Kateryna Kublytska discusses the damage to the architecture of Kharkiv, while situating the ongoing destruction within a broader discourse of heritage protection in Ukraine and the contested question of de-russification. Olena Mokrousova’s text further scrutinises the subject of de-communisation, contemplating how the process has been recast since February 2022. Collectively, these pieces suggest that what makes Ukrainians a nation is not only their history and language, but also the vision of the future that they are taking action to build today.

Ukrainian Wartime Art: Anti-Colonial Resistance in a Decolonial Age // By Svitlana Biedarieva

Svitlana Biedarieva is an art historian, curator, and artist. The focus of her current research is contemporary Ukrainian art, decoloniality, and Russia’s war against Ukraine. Svitlana holds a PhD in History of Art from the Courtauld Institute of Art. In 2019-20, she curated the exhibition At the Front Line. Ukrainian Art, 2013-2019 in Mexico and Canada. She is the editor of Contemporary Ukrainian and Baltic Art: Political and Social Perspectives, 1991-2021 (Stuttgart: ibidem Press, 2021) and co-editor (with Hanna Deikun) of At the Front Line. Ukrainian Art, 2013-2019 (Mexico City: Editorial 17, 2020).

The war of Russia against Ukraine that began in 2014 and escalated into a full-scale invasion on 24 February 2022 has caused the revival of anti-colonial resistance. Ukraine was part of the Russian Empire from 1765 to 1917 and then became a republic in the Soviet Union. For Ukrainian culture, the post-Soviet period was marked by the final break of colonial bonds and intensive postcolonial development, which was characterised by the reconstruction of identities and cultural revival. The last three decades have also paved the way for the final decolonial transformation.

The decolonial researcher Madina Tlostanova distinguishes between postcoloniality and decoloniality not only from a paradigmatic point of view – such as the postcolonial theory that was developed by Indian theorists Homi Bhabha and Gayatri Spivak and the decolonial theory by Latin American scholars Walter Mignolo and Aníbal Quijano – but also from a chronological perspective.[14] The postcolonial development in this model immediately follows the anti-colonial resistance and the resulting downfall of an empire, when a society of a now-independent country reworks its recent colonial experience. The decolonial process, however, goes one step further through liberation from any colonialist connotations.[15] Ukraine’s defence against Russia’s full-scale war of aggression in 2022 constitutes the decolonial stage of release from both colonial bonds and postcolonial hybrid and ambivalent narratives.[16] The processes of decolonial release in Ukraine gained the radical characteristics of an initial anti-colonial struggle after the outburst of Russian violence. This arose from witnessing the atrocities performed by the Russian army in Ukraine and the necessity to reject the false claims of a historical Russian-Ukrainian ‘brotherhood’ that are projected onto today’s situation. This merging of the anti-colonial and decolonial stages is paradoxical for contemporary decolonial studies. George J. Sefa Dei and Meredith Lordnan, for example, present the ‘decolonial’ as a critique and reformulation of the ‘anti-colonial’, as well as its final goal; for them, these two options cannot coexist in one timeframe.[17] But such an anachronistic phenomenon, as is that forced onto Ukraine by the war, is recorded and reflected in the works of contemporary Ukrainian artists.

With the once-dominant narrative of Russian culture ‘enveloping’ Ukrainian culture irrevocably disintegrating, many artworks propose to reconsider Ukraine’s relation to Russian culture and society through a new radical perspective. The present-day anti-colonial focus in Ukrainian art serves to delimit the space of Ukraine’s symbolic territory while nearly twenty per cent of its geographic territory is occupied by Russia. Such resistance, therefore, is seen widely to be a matter of cultural defence. The dichotomy of anti-colonial/decolonial processes in the case of contemporary Ukraine presents a paradox, since it embraces decoloniality as the final release of the colonial narratives, resulting from thirty years of Ukrainian independence. However, the new wave of anti-colonial resistance has further triggered decolonial processes and growing opposition to new practices of colonial domination undertaken by Russia. The recent strategy in Ukrainian art has been to step back from the post-colonial situation to exercise a temporarily anti-colonial perspective. The aesthetics of protest posters permeate the artworks created after February 2022. ‘Wartime art’ would be the most appropriate definition for the entire body of works that have been produced in Ukraine in the last five months.

Painter Vlada Ralko’s recent work, The Dove of Peace Rapes a City (2022, Fig. 1) merges drawing with watercolour painting on paper to meditate on the full-scale invasion. The drawing presents Russia’s coat of arms as a double-headed monster shelling a Ukrainian city, with skulls instead of eagle heads and pigeon wings. Here, a destroyed city becomes equal to a suffering human body, echoing the rape committed by Russian soldiers in the Kyiv suburbs. A phallic form of the missile highlights this parallel. The parallel between the corporeal experience of torture and agony and the destruction of urban space becomes the focus of the entire series of the artist’s work.

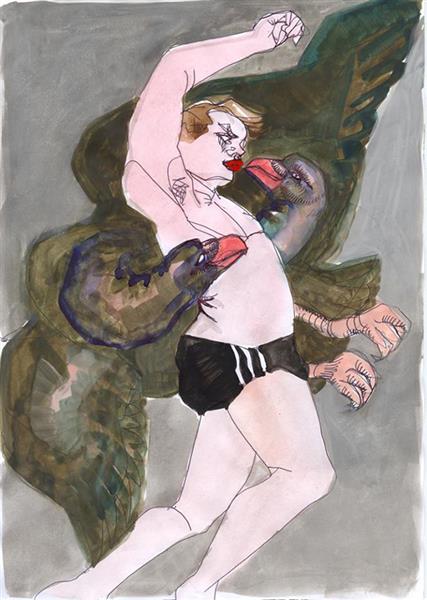

This drawing also refers to the artist’s earlier works and reflects the violence performed by the two-headed Russian eagle that Ralko depicted in her series Kyiv Diary between 2014 and 2015. The visual diary of the artist at that time documented what can be seen now as an anti-colonial struggle of the Maidan protests, which were staged against the pro-Russian puppet government of Victor Yanukovych.[18] Drawing No. 174 (Fig. 2) shows a male figure caught between the two heads of the eagle that attacks and abuses him, ironically alluding to the myth of Leda and the swan.[19] While the apparent violent intentions of the eagle in the Kyiv Diary series are portrayed figuratively, in the new work from 2022, the state emblem of Russia loses any anthropomorphic features, becoming a macabre machine of pure evil, corresponding to the atrocities performed by the Russian collective body as represented by Russia’s army.

Ralko speaks about this profound postcolonial hybridity of the events of 2014-2015:

I was mesmerised by the ultimate integrity of the reality unfolding in front of us. One could no longer turn to the familiar criteria and separate the high from the low, the heroic from the cowardly, the beautiful from the ugly. […] Not only moments of real-time, but also parallels between them were made manifest, all the ties between the times of turmoil and peace: people planted potatoes and buried their dead with equal diligence, and the same landscapes could become a backdrop for hostilities and peaceful life.[20]

The most recent Ukrainian art should not be dated by year but rather by month or by week as the works trace, in an impromptu manner, the changing attitudes towards Russia’s desire for colonisation with the unfolding of violence since February 2022.

Alevtina Kakhidze’s series of works saw a massive transformation within one-and-a-half months. The drawing Self-portrait (Fig. 3), made ten days before the invasion began on 24 February, depicts the artist surrounded by weapons. On the left, Kakhidze presents charged questions about her well-being and defence weapons as gifts from the allies; on the right, she shows Russian weapons directed at her. The artist reflects on the helplessness and uncertainty that marked the last days before the invasion. While the western side is presented as figurative, with a human face, Russia is shown as a hostile, faceless entity aimed at killing. By showing herself as a target, Kakhidze highlights the state of vulnerability that all Ukrainians experienced in the months leading up to the full-scale attack.

The drawing Russian Culture Looking For an Alibi That It Is Not a Killer (Fig. 4) from late March 2022, however, is already more direct and condemning. It shows another two-headed monster comprised of the figures of Lev Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky. This hybrid creature crawls forward to the west, with the cat of Joseph Brodsky in the vanguard, supported by four legs of the Swan Lake ballet dancers as a reference to an approaching coup. Such a grotesque depiction marks an intersection of naïve art with a political art poster. Kakhidze’s work resonates with Ralko’s drawings in its radical anti-colonial expression and further develops the topic of abuse in a call to see Russian imperial culture at the roots of both the inhuman actions of the Russian army in Ukraine and the popular support of military violence among the Russian population.

Confronting the totality of Russian culture in a drawing can be likened to challenging a Russian tank with nothing but a Molotov cocktail. In both cases, the imbalance in power positions is compensated by the courage of the action. The straightforwardness of the recent political art is conditioned by the necessity to contrast two symbolic spaces of power: the fading power of the former oppressor and the emerging power of the formerly oppressed, now acting as an independent and self-sufficient entity.

However directly anti-colonial the works of Ralko and Kakhidze might seem, the decolonial impulse can be felt in their latest wartime drawings, showing that the anti-colonial resistance that Ukraine has been forced into is only a means for true decolonial release. The contemporary Ukrainian case presents a paradox with the anachronistic anti-colonial fight unfolding in front of witnesses and direct participants, leaving no space for moderates in the matter of defence against invasion. The interpretations by Ralko and Kakhidze with a direct reference to Russia as a colonial power, thus responding to both the current violence and past traumas, while commenting on the gap between the two nations that has become wider ever since the outburst of Russian violence in the Ukrainian territory. Moreover, the artists’ drawings predicted the decolonisation campaign that is now unfolding in Ukraine. This campaign entails the revision of strategies that form the Ukrainian cultural sector such as bolstering publishing books in Ukrainian while significantly reducing the dissemination of literature from Russia. It may also entail a public focus on a more profound mass study of Ukraine’s history with the reconsideration of the imperialist elements inherited from the Soviet historiography.

Interview // In Conversation with Kateryna Kublytska[21]

Kateryna Kublytska is a practicing architect and restorer, a laureate of the State Prize of Ukraine in Architecture (2011). She is a member of Urban Forms Centre, a non-governmental organisation that specialises in sustainable urban and community development, and research of the architectural and cultural heritage of Ukraine. Kateryna is also an active participant of ‘Save Kharkiv’, an initiative group for the protection of the city’s cultural heritage. In her own research, she focuses on the architecture of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the evolution and relationship between Art Nouveau and interwar modernism. For 2022-23, Kateryna is the Samuel H. Kress Foundation Visiting Fellow at The Courtauld Institute of Art.

Tell us a little bit about your work before the full-scale war. What led you to architectural preservation?

I was introduced to architectural restoration from almost the first days of my undergraduate studies since I trained as an architect-restorer. But in terms of having a strong civic position and performing community work, my involvement started in earnest in 2017-18. I worked as a consultant for the documentary film Save cannot be destroyed and participated in the USAID-sponsored project ‘Law on the Protection of Cultural Heritage’ in partnership with the charitable foundation ‘Kharkiv with You’. As the project’s name suggests, we proposed changes to Ukraine’s legislation on cultural heritage. This was a catalyst moment that brought together like-minded professionals in Kharkiv, who started educational activities aimed at informing the public on the topics of heritage. But mostly we had to deal with emergency cases when property developers disregarded norms of preservation and historic buildings were to be unlawfully reconstructed. In these cases, we created campaigns for public appeal and worked with the city authorities to ensure adherence to the standards.

I imagine that such projects can be quite long-term and they, therefore, disappear from the media coverage. Did you have any success stories with retaining public attention?

There was one exceptional case when pretty much the whole of Kharkiv revolted against the proposed intervention on Maidan Svobody (Freedom Square).[22] The city’s chief architect decided to erect a monumental column, featuring an angel and a cross, right in the middle of the modernist ensemble, which was largely constructed in the inter-war period of the twentieth century (Figs. 5-6). To put it mildly, this monument did not quite fit with the square’s overall architecture. There was a lot of attention and a public outcry, and the project was stopped. But this is an atypical case when the publicity was far-reaching. Normally, we have to deal with single historic buildings that property developers decide to rebuild, either in part or entirely, or to change the façade décor, disregarding all norms. The ensuing court cases can go on for years and they do not always attract public attention.

What is the overall state of legislation in Ukraine when it comes to the protection of architectural heritage?

This is a very complex question and there are various issues. The main problem is that the legislation on heritage has not been reviewed and updated since the early 2000s, so it is full of atavisms. In theory, the existing legislation stipulates what can and cannot be done, but the used wording is loose and open to interpretation. Furthermore, the procedures for pressing charges, when the norms are not met, are ill-defined. So, for example, the law says that when it comes to immovable heritage only restoration can be applied, not reconstruction. Noncompliance in such cases is considered a criminal offence, but I am not aware of a single precedent when the reconstruction of a historic building led to criminal charges against property developers and contractors.

Another issue is that Ukraine’s legislation can be defined as that of only sticks without any carrots. When we speak about architectural heritage, we talk about large sums of money and very long timeframes. But the current climate in Ukraine does not incentivise investors. The processes are extremely bureaucratic and there are a lot of standards to adhere to, but nothing to receive in return. This is different in western Europe and the USA, where the legislation on architectural preservation is linked to taxation and there are various incentives for owners and property developers, including tax breaks and suspensions, as long as they comply with the norms.

Unsurprisingly, the situation is more complicated now due to the full-scale war. I know that you continue your volunteering activity in Kharkiv, what kind of projects have you been working on since February?

I was eager to get involved from the very first days, but it was obviously extremely dangerous and very few people were given access to the ruined buildings. It was not feasible to even go out onto the streets, let alone rummage damaged sites. What I was trying to do, and I am still doing, is to raise awareness, especially among the officials and public servants, since the general public as such has dispersed due to mass emigration and internal dislocation. I am reiterating that work with the debris of historic buildings, once pyrotechnics and criminal investigators have processed it, should not be approached in the same way as for other sites. This kind of debris is not your regular construction waste. Relevant specialists should be present on-site to document the damage and collect materials that could be used in restoration. Non-specialists, for example, would not know that the wood used in ceiling beams is exceptionally valuable, especially in the buildings constructed before the 1940s; it should be preserved as donor material for future restoration and not burned. Of course, such a careful collection of building and decoration materials creates extra work for the city services, but we are talking about a handful of buildings among hundreds that are destroyed and damaged.

Sadly, my colleagues and I did not have a chance to intervene early on and in some cases, debris was disposed of as rubbish. But we were able to oversee the process for buildings that were shelled more recently. Following the initiative from the Ministry of Culture that the Kharkiv city authorities have supported, I visited the sites to assess the damage and create reports following the ICCROM standards, which is part of recording war crimes and building cases for subsequent persecution in international courts.[23]

Can you describe one of the damaged historic buildings that you have inspected?

Yes, the building of the Kharkiv regional state administration, located on that same Maidan Svobody, was shelled in early March (Figs. 7-8).[24] While one part of the building was hit directly by a missile and ruined, the overall structure has survived and is still standing. I visited the site together with a team of colleagues to undertake a complex inspection – visual, laboratory, and technical – to ensure the safety of the surviving construction and assess the level of damage. We concluded that while some level of structural reinforcement was required, the building nonetheless could be restored as long as it is properly conserved until the end of the war – the roof covered, windows and door openings sealed off, and damaged areas strengthened to protect the walls from collapsing. The city authorities, however, announced in June, completely out of the blue, that the building was so severely damaged that it could not be restored and will need to be demolished.

What do you think has led to such a stance?

We have a layer of inconvenient, or uncomfortable, heritage in Ukraine. Our society is extremely hurt right now and we are overly sensitive and vulnerable. And all these emotions are manifest in our collective attitude towards tangible heritage. The processes of de-communisation and decolonisation are currently in full swing and, in theory, the Ministry of Culture has decreed to set up a special commission to deal with these aspects, but it is yet to be established. Society, however, demands changes and it wants them now. This leaves little time for proper investigation, reflection and analysis, and local authorities succumb to populist solutions. But after our consultations with the Kharkiv city authorities, they now recognise the possibility to restore the regional administration building and even advocate for such a solution.

This is a real wartime success story! What is your professional take on the buildings that are perceived as part of this inconvenient heritage?

Our local architecture, even those examples that were created during the detested Soviet years, is different from the examples in Russia or the Union at large. There are a lot of elements that are uniquely our own, connected to the style of Ukrainian Baroque or the ornaments used in Ukrainian folk embroidery (Fig. 9).[25] So the story here is not about Stalinism or imperialism. Even in the east of Ukraine, in such cities as Kharkiv and Zaporizhzhia, we can observe architects’ attempts to re-think and move away from the communist symbolism. I now understand why, according to Ukrainian law, a building can be declared a heritage site only seventy years after its creation. We, as a society, need this time to come to a more detached assessment and understanding unbiased by past traumas. At some point, there was a very sceptical and negative attitude towards our Art Nouveau architecture, which seems unimaginable now. Then, there was a lack of understanding of the inter-war styles, including Constructivism, which are appreciated by a much broader audience today. Now, this wave of misapprehension has come to the buildings of the 1940s-50s. The epoch of Socialist Realism is currently perceived with pain and negativity.

I see a lot of this attitude in the visual arts as well, when everything that was created during the Soviet Union, after the 1920s, is automatically rejected.

Indeed, and I think what adds to the complexity is the lack of understanding in our society of what heritage is. During the Soviet era, the concept of heritage, which is linked to the idea of ownership, was beaten out of our people. So for generations, our society has been programmed to lose this link, this connection with the past. Only now, we start internalising heritage: when our historic buildings are shelled, it is impossible not to feel pain, very often quite physical. Also, we have started to connect to heritage in a more personal way. With the building of the Kharkiv regional administration, for example, I have read comments of people whose parents worked on its construction after World War II. And there are also those whose great-grandparents designed the original building that was there during the Russian Empire. So when we talk about heritage, we should not only refer to the buildings themselves and their aesthetic qualities, but we need to know and remember the stories of people, who were connected to these sites. And you come to realise that on the one hand, yes, this heritage might be inconvenient or contested, but, on the other, it was created by generations of Ukrainians. Buildings are also part of the fabric of the city and the region, showing the development of local architecture and engineering. The fact that a building survived through the last eighty or so years, not the most peaceful, is a testament to the engineering thought and technical expertise of the people who constructed them.

This reminds me of the idea of respecting the city in its historical context that you mentioned in one of your previous interviews. What is your proposed solution to the issue of inconvenient heritage?

We need to reframe how we address public opinion in this case. I think that heritage is a scientific question and, while society needs to be consulted and educated, specific cases should be debated by specialists and not so much in the public sphere. For example, one of the damaged buildings that I inspected was the 1920s edifice of the Kharkiv University of Arts (Figs. 10-11). I think I might have visited it as a child, but I had no recollection of its interiors. At first, I was amazed to see all this luxury, the unexpected luxury of the 1920s, which is close to Art Deco with its expensive austerity and aesthetic asceticism. And then it dawned on me that in the 1920s-30s this building headquartered the trade exchange, which was the place for selling the confiscated property of the Ukrainian nobility and kulak peasants, all those things that the Bolsheviks, frankly, had looted from our people, killing them in the process.[26] So this building is directly linked to a very bloody chapter of Ukrainian history. Emotionally, I was terrified since it was also the fate that befell members of my own family. And if I were to make an emotive decision, I would probably suggest that the building should not be restored. But at the same time, I recognise that I have a claim to this building, it is part of my personal history that I have to know and remember. And this is the case for everything that was built during the Soviet Union – this is our heritage, whether we like it or not.

With all of these issues and concerns in mind, how do you see the post-war rebuilding of Kharkiv? There have been multiple declarations from international architects, pledging to help restore and rebuild Ukraine after the war. What is your take on this?

I have quite a complicated attitude towards such claims. On the one hand, I want to say ‘Wow! That’s great, let’s do it!’ But, on the other, I am conscious that Ukraine can turn into a site of experimentation for international architects, while we will have to live with all of it afterwards. So there is a very fine line to be maintained.

We also have to understand that we do not yet know what kind of city Kharkiv will be after the war. It will not be the same city as before. In the future, we will be more acutely aware of its location so close to the Russian border, which will influence the new infrastructure and look of the city. The experience of the war will have to be regarded in the rebuilding process and military experts will have to be consulted. A lot of research – sociological, military, and economic – needs to be completed to inform the rebuilding strategy. And this will require time, possibly years. After the Second World War, it was estimated that it would take no less than sixty years to rebuild Kharkiv and restore its economy. And that is exactly how long it took. Such processes will be quicker this time, but they will nonetheless be long and we have to prepare ourselves mentally that they will take years, not months.

But it is only human to want to rebuild quickly, it is a psychological device that allows us to accept the destruction. Let’s end with something positive, do you have any good news to share from Kharkiv?

I want to highlight all the aid that we receive from the international community and NGOs. Recently, we acquired a 3D scanner for our local department of preservation. There is little experience in Ukraine of working with 3D laser scanning and I am grateful to Emmanuel Durand, a French Zurich-based structural engineer, who came to Ukraine amid the war to produce 3D models of some of the damaged historic buildings. Emmanuel brought his own device and showed us how to use it (Fig. 12).[27] With the help of the local Kharkiv charity Toloka, we managed to secure funds to buy a 3D scanner for the city. It has already been a game-changer for the immediate documentation of the damage. And it will also be invaluable for scanning yet undamaged buildings, creating a database that could be used in the future. Projects like this with international support are crucial since they draw attention to Ukraine’s cultural identity, while also showing us, Ukrainians, that we are not alone in this war.

De-Communisation: The Ukrainian Perspective // By Olena Mokrousova

Olena Mokrousova is an architectural historian and preservationist. She holds a PhD in the field of museology and cultural heritage. For the last 25 years, Olena’s research has focused on the nineteenth and twentieth-century architecture of Kyiv. As a leading expert, she has actively contributed to the work of the Kyiv Centre for the Protection, Restoration and Use of Monuments. She is a member of the Ukrainian branch of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and Docomomo International, a non-profit organisation for the protection of modern architecture and urbanism.

The debate is not about the past, it is about the present. What kind of society are we today? Are we a society fragmented by past ideologies or are we a democratic and pluralistic society that believes in tolerance and respect?

[…] the idea that monuments should not be destroyed, but rather radically transformed is powerful. It encourages people to reflect on history, question ideology and critically assess the present. – Hannes Obermair[28]

The war in Ukraine has not only affected the everyday life of its citizens but the trauma is also manifest in the Ukrainian society’s attitude towards its tangible and intangible cultural heritage. The re-evaluation of historical narratives and material culture commenced in Ukraine a long time ago, but recently these processes have undergone a fundamental transformation that will determine the country’s post-war consciousness. The aggressive actions of the Russian occupiers towards Ukrainian culture have demonstrated how fragile its heritage is. Such a realisation prompted an increase in the number of people who are ready to fight for its preservation, overcoming the country’s colonial past by changing its cultural landscape. However, such activities carry certain threats to further societal development.

De-communisation in Ukraine – the process of removing the consequences of communist ideology – began thirty years ago with the collapse of the Soviet Union. It proceeded in several stages. First, monuments to the communist regime were demolished as early as 1991. Second, a 2009 decree by Ukraine’s President Viktor Yushchenko initiated the general dismantling of monuments and signs dedicated to individuals involved in the organisation and implementation of famines and political repressions during the Soviet era. Third, in the early days of the Maidan Revolution, the central monument to Vladimir Lenin was toppled in Kyiv. This caused a chain reaction, the so-called ‘Lenin Fall’, during which monuments to Soviet statesmen and Soviet symbols were destroyed en masse. A year and a half later, in the spring of 2015, a series of four laws were implemented that have been unofficially branded as ‘de-communisation laws’. These laws collectively dealt with such issues as the prohibition of monuments related to the communist and Nazi regimes; the honouring of the twentieth-century fighters for Ukrainian independence; the remembrance of the victory over Nazism in World War II; and granting access to the archives of repressive bodies of the communist regime. Volodymyr Viatrovych, historian and the head of the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory (itself founded at the end of 2014, in the aftermath of the Maidan Revolution), initiated the introduction of these laws. Despite the Institute’s name and its various research activities, it is an executive body that implements state policy concerned with the restoration and preservation of the Ukrainian people’s national memory. It is, therefore, mainly an ideological body.

The announcement of these laws was met with significant criticism. David R. Marples, Canadian historian and professor at the University of Alberta, together with a group of sixty-eight Ukrainian and international scholars, experts and professors called on President Petro Poroshenko not to sign the bill. In their opinion, these laws would politicise history, contradicting the fundamental right to freedom of expression, and would thus encourage Ukraine to follow Russia’s undemocratic path. In December 2015, the European Commission for Democracy through Law (The Venice Commission) determined that the laws did not meet the Council of Europe’s standards. The Commission gave several recommendations that would bring the bill in line with these standards. Nevertheless, President Poroshenko enacted the laws in May 2015. Additionally, the activity of the Communist Party of Ukraine was banned by a court order in December 2015.

Consequently, since 2015, the de-communisation in Ukraine has taken place within the framework of the newly introduced legislation. According to the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, 51,000 toponymic names were changed in five years and approximately 2,500 monuments and signs were dismantled or removed from public spaces. These processes, however, engendered relentless public discussion: while some deemed them too slow and bureaucratised, others highlighted the need for a more in-depth study and balanced attitude towards historical objects. At the same time, the new laws limited the effect of de-communisation on monuments related to the Second World War, in which Ukraine participated as part of the Soviet Union and lost the largest number of inhabitants.[29] To add to the complexity, some monuments and architectural sites are classified as heritage objects, a legal status that protects them from being overruled by the de-communisation laws.

The most heated debates in Kyiv appeared around the de-communisation of the Shchors monument. Mykola Shchors (1895-1919), the commander in the Red Army, fought against the Ukrainian People’s Republic and was briefly the military commandant of Kyiv under the Bolsheviks in 1918. During Stalin’s rule, the figure of Shchors was heroised and mythologised with monuments erected to commemorate his legacy. Following the new laws, the monument to Shchors had to be dismantled. There was a problem, however: the statue had the legal status of a monument of national significance. Arguably, it is indeed one of the best equestrian statues in Ukraine, created in 1954 by a team of Ukrainian sculptors headed by Mykola Lysenko (1906-1972). Many historians, art critics, and specialists in the field of monument protection came forward to defend the sculpture as a work of art. In the end, the monument was saved bar the leg of the statue’s horse that a group of unknowns sawed off in protest.

What motivates such an iconoclastic attitude? One of the main reasons is the perception that the monuments on the city streets and squares are symbols of the past, that they are instruments of Soviet propaganda with no place in the revised history of contemporary Ukraine. There is a widespread belief that until the public space is completely cleansed of the ‘ghosts of communism’, people’s consciousness will continue to be poisoned, which in turn will prevent the arrival of a new era in the history of Ukraine. It seems to me that this is how the archaic magical thinking of mankind manifests itself: from ancient times, images or names were destroyed because they were believed to be the personification of enemies, with their annihilation thus shifting the balance in power. Most historians understand that it is impossible to erase history, even if one does not like it, and Ukrainian society has already experienced a similar erasure under the Soviet regime. But for many, eradication appears to be an appropriate and efficient solution. Public consciousness is not ready to re-think the historical experience and the trauma of the current war does not contribute to equanimity and tolerance.

There are examples of other approaches to contested cultural spaces. An innovative and democratic way to modernise the architectural heritage of fascism was found in the north-Italian city of Bolzano. There, a group of historians and artists gathered in 2014 to discuss the building of the tax office, which features a giant bas-relief depicting the rise of Italian fascism, and the Arch of Victory, which contains symbols of the fascist regime. Hannes Obermair, professor of modern history at the University of Innsbruck and one of the experts tasked with solving the problem, recalls that ‘the choice was between total destruction and preservation. But when you destroy monuments, you remove evidence thus negating the possibility of a dialogue with complex layers of history and identity.’[30] In the end, a creative solution was found that defused the tension and allowed for the unification of the city’s Italian and Tyrolean communities. Experts proposed to re-contextualise the buildings, preserving their artistic integrity and historical importance while neutralising and undermining their fascist rhetoric.

Ukraine, however, was not ready for such an exercise even before the full-scale war of 2022, even though the society as a whole and the most ardent opponents of the Soviet symbolism agreed with art historians that artworks of the Soviet period should be removed from the urban space but preserved in appropriate institutions. In 2014, the idea of creating a Museum of the Soviet Era or a Museum of Totalitarian Art was voiced. Such a suggestion came twenty years too late. A similar sculpture park, called Memento (Szoborpark in Hungarian), was set up in Budapest back in 1993 to showcase monumental statues and sculpted plaques from Hungary’s communist period (1949-1989). The park’s architect, , Ákos Eleőd, described his design as being ‘[…] dedicated to dictatorship and, at the same time, since we can talk and write about it, to democracy. After all, only democracy makes it possible to speak freely about dictatorship.’[31] Similar parks and museums have been established in other countries, such as Lithuania and Bulgaria.

In 2017, the Kyiv city authorities declared that the Shchors monument would become the first exhibit of a new Museum of Monumental Propaganda of the USSR, which was to be opened in the capital. Then Minister of Culture Yevhen Nyshchuk promised that relevant objects would be collected from all over Ukraine to be displayed in the museum. The project, however, remains unrealised to this day with uncertain prospects for its completion. There is also a danger that such a space would simply act as a dumping ground for all ‘Soviet junk’. To undertake a project of this scale properly would require not only political will, but also significant funds and the involvement of specialists from various fields.

The new phase of Russia’s war on Ukraine has left almost no room in Ukrainian society for such discussions. At the same time, the complex process of de-communisation, which remains incomplete, is aggravated by the need for de-imperialisation with the entailing call to cancel Russian culture. Against the backdrop of war crimes committed by Russians against Ukrainians and their culture, the question of responsibility placed on the culture of the aggressor has turned into an acute practical challenge in documenting the war. The main question today is whether it is possible to re-think one’s heritage without resorting to the out-dated methods of re-writing history. Is it possible to overcome colonial insecurities and form a modern political nation while acknowledging and embracing some of the uncomfortable episodes in the country’s history? In contrast to de-communisation, Ukraine has no laws on de-Russification and de-imperialisation. Further, there are no clear criteria for such a process beyond the rather arbitrary idea of the national and political affiliation of historical and cultural figures. Therefore, even during the war, these discourses prove divisive for Ukrainian society.

In an attempt to defuse the tension arising from the aforementioned public debates, the Ministry of Culture and the Institute of National Memory announced that de-communisation would continue. But a complex re-thinking of Ukrainian historical and cultural heritage and the development of relevant societal narratives must accompany the cleansing of public space from the markers of imperial claims. The dismantling of monuments and toponymic re-naming should be carried out under Ukrainian legislation. But also, as noted by the current Minister of Culture Oleksandr Tkachenko, the conclusions of scientists and independent experts regarding the historical and artistic value of objects under de-communisation must be taken into account. The Ministry also agrees that some objects require a re-configuration of the cultural context with their relegation to the future museums of propaganda. As the art historian Yevheniia Moliar has noted, it is extremely important to demonstrate to the world a new method of working with the tragic past of Ukraine – a civilised one without destruction and vandalism that would finally free Ukrainians from the dictates of Soviet propaganda.[32]

Citations

[1] I approach the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union as two iterations of Russia’s imperial ambition.

[2] As per the report issued on 30 August 2022, https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/damaged-cultural-sites-ukraine-verified-unesco (last accessed: 31 August 2022).

[3] According to the report posted by the Ministry of Culture and Information Policy of Ukraine on 22 July 2022 https://www.kmu.gov.ua/en/news/mkip-rosiia-zdiisnyla-vzhe-434-zlochyny-proty-kulturnoi-spadshchyny-ukrainy (last accessed: 31 August 2022).

[4] This myth was the cornerstone of the so-called Synopsis, printed in 1674 and used in the pre-modern Russian Empire as its first historical textbook. The impetus behind the creation of this myth was the need for Russia’s (Muscovy at the time) protection when Kyiv faced repeated assaults from the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Poland. By presenting Kyiv as the birthplace of Muscovy, the claim was made that the city could not be abandoned to infidels or Catholics.

[5] This ‘Lenin theme’ was first introduced in Putin’s speech on 21 February 2022 that served to justify his authorisation of the so-called special operation, de-facto war, in Ukraine. Serhii Plokhy explores the historical misapprehensions that led to the appearance of this narrative in his article ‘Casus Belli: Did Lenin Create Modern Ukraine’, News Portal of Harvard University’s Ukrainian Research Institute (Published: 27 February 2022, last accessed: 15 August 2022, https://huri.harvard.edu/news/serhii-plokhii-casus-belli-did-lenin-create-modern-ukraine).

[6] Ivan Rudnytsky explores this claim in his Essays in Modern Ukrainian History (Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, 1987). In its modern reading, the concept of ‘non-historical nations’ was developed by Friedrich Engels when examining the nationality problem within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Engels, in turn, borrowed this idea from Hegel, who associated nationhood with a tradition of statehood. For a historical account, see Roman Rosdolsky, Engels and the ‘Non-historic’ Peoples: The National Question in the Revolution of 1848 (Glasgow: Critique Books, 1986).

[7] Chief among them was Taras Shevchenko, a Ukrainian poet, writer, artist, and activist. Shevchenko, who was one of the most vocal proponents of the Ukrainian national idea of his generation, is credited as the founder of modern Ukrainian literature. For an insightful overview of how Ukrainian writers have for centuries fought against Russian imperialism and colonialism, see Uilleam Blacker, ‘What Ukrainian Literature Has Always Understood About Russia’, The Atlantic (Published: 10 March 2022, last accessed: 3 October 2022https://www.theatlantic.com/books/archive/2022/03/ukrainian-books-resistance-russia-imperialism/626977/).

[8] For an exhaustive yet digestible presentation of Ukrainian history, see Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine (London: Penguin Books, 2015). For a more condensed account, see Timothy Snyder’s essay ‘The War in Ukraine is a Colonial War’, The New Yorker (Published: 28 April 2022; last accessed: 15 August 2022 https://www.newyorker.com/news/essay/the-war-in-ukraine-is-a-colonial-war).

[9] Terry Martin’s The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923–1939 (Ithaca; London: Cornell University Press, c2001) provides a detailed analysis of the policy’s goals and outcomes throughout the USSR.

[10] Boris Groys, ‘Beyond Diversity: Cultural Studies and Its Post-Communist Other’, in Art Power (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2013), 155.

[11] Groys, ‘Beyond Diversity’, 156.

[12] Useful sources on the resurgence of national identities in other post-Soviet states include Pål Kolstø, Political Construction Sites: Nation Building in Russia and the Post-soviet States (New York: Routledge, 2018); and Rein Ruutsoo, Civil Society and Nation Building in Estonia and the Baltic States. Impact of Traditions on Mobilization and Transition 1986-2000: Historical and Sociological Study (Rovaniemi: Lapin yliopisto, 2002).

[13] Plokhy, The Gates of Europe, xxii.

[14] Madina Tlostanova, ‘The Postcolonial Condition, the Decolonial Option and the Post-Socialist Intervention’, in Monika Albrecht (ed.), Postcolonialism Cross-Examined: Multidirectional Perspectives on Imperial and Colonial Pasts and the New Colonial Present (London and New York: Routledge, 2020), 165, 165-178.

[15] It is important to mention that neither postcolonial theory – nor decolonial theory in its original Latin American view – is fully applicable in the case of Ukraine as part of Eastern Europe. Attempts to apply decolonial theory to the post-Soviet and Eastern European contexts have been done by Madina Tlostanova and Walter Mignolo, for example, in the book Learning to Unlearn Decolonial Reflections from Eurasia and the Americas (Columbus: The Ohio State University Press, 2012). However, in my opinion, geographical, political, and racial context requires a separate theory that would describe the differing decolonial dynamics in the regions – to be developed in the future.

[16] These narratives, as defined by Homi Bhabha, represent the construction of mixed transcultural identities, often containing conflictive elements belonging to the oppressing and the oppressed cultures. Homi Bhabha, ‘Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse’, Discipleship: A Special Issue on Psychoanalysis, special issue, October, no. 28 (Spring 1984), 125–133, https://doi.org/10.2307/778467 (Last accessed: 23 June 2022). See also, Svitlana Biedarieva, ‘Decolonization and Disentanglement in Ukrainian Art’, post MoMa (Published: 2 June 2022, last accessed: 19 June 2022, https://post.moma.org/decolonization-and-disentanglement-in-ukrainian-art/).

[17] George J. Sefa Dei and Maredith Lordnan, ‘Envisioning New Meanings, Memories and Actions for Anti-colonial Theory and Decolonial Praxis’, in George J. Sefa Dei and Meredith Lordnan (eds.), Decolonial Theory and Anti-colonial Praxis (New York: Peter Lang, 2016), vii-viii, vii-xxi.

[18] Maidan Revolution, also known as the Revolution of Dignity, took place in Ukraine in January-February 2014 as a popular protest against President Viktor Yanukovych’s policy of pursuing closer ties with Russia as opposed to European integration. The ensuing deadly clashes between protesters and the security forces in Kyiv culminated in the ousting of elected President Viktor Yanukovych, leading to a Russian military intervention with the illegal annexation of Crimea and the outbreak of the Donbas War.

[19] In the Greek myth, Zeus raped Spartan queen Leda in an ambiguous appearance of a swan.

[20] Vlada Ralko and Taras Voznyak, Kyivskyi shchodennyk (Lviv: Borys Voznytskyi Lviv National Art Gallery, 2019), no page.

[21] I am grateful to Dr Robin Schuldenfrei at the Courtauld Institute of Art for facilitating this interview and drawing my attention to some of the aspects of architectural preservation that needed to be addressed in our conversation with Kateryna.

[22] The central square of Kharkiv, Maidan Svobody is the sixth largest square in Europe and the twelfth in the world. It was mostly constructed throughout the 1920s and features, among others, the Derzhprom building, a prime example of constructivist architecture. Derzhprom, or the House of State Industry, was built in 1926-28 as one of the first skyscrapers in Eastern Europe and the first building made of reinforced concrete monolith. Russian missiles hit Maidan Svobody and its surroundings in early March 2022 in their failed attempts to seize Kharkiv.

[23] The International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM) is an intergovernmental organisation dedicated to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide.

[24] The building of the Kharkiv regional state administration was erected in 1951–54 based on the designs of Ukrainian architects Veniamin Kostenko and Volodymyr Orekhov. While the building’s overall style is that of the Stalinist Empire, sometimes also referred to as Socialist Classicism, elements of Ukrainian folk architecture were nonetheless used in its stucco decorations.

[25] Ukrainian Baroque, also known as Cossack Baroque, is an architectural style that was widespread in Ukrainian lands in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It emerged as a combination of local architectural traditions and European Baroque.

[26] Kulak, in Soviet history, was a wealthy or prosperous peasant, generally characterised as one who owned a relatively large farm and was financially capable of employing hired labour and leasing land. Kulaks actively opposed the policy of forced collectivisation launched by Stalin in the late 1920s. As the result, most kulaks – as well as millions of other peasants who had opposed collectivisation – had been deported to remote regions of the Soviet Union or arrested with their land and property confiscated. For an exhaustive overview of these processes in Ukraine, see Anne Applebaum, Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine (New York: Anchor Books, 2018).

[27] For the description of Durand’s project and some of the 3D models that he created in Ukraine, see Mark Doman, Thomas Brettell, and Alex Palmer, ‘Culture in the Crosshairs’, (Published: 24 August 2022, last accessed: 28 August 2022 https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-08-25/the-hi-tech-3d-fight-to-save-ukrainian-culture-from-destruction/101262720?utm_campaign=abc_news_web&utm_content=link&utm_medium=content_shared&utm_source=abc_news_web)

[28] Hannes Obermair quoted in Alex Sakalis, ‘Demolish or Preserve? What to Do with the Architectural Heritage of Fascism’, BBC Culture Ukraine (Published: 7 February 2022, last accessed: 1 July 2022, https://www.bbc.com/ukrainian/vert-cul 60250579?fbclid=IwAR115Q_cZiNj9zPA8XLrNZNhecp7 pAvHgaz_ekHyzbquL2l9EjqTVyJp1o).

[29] The official estimate is that Ukraine lost up to seven million of its citizens (15% of its population) during the Second World War. Plokhy, The Gates of Europe, 291.

[30] Obermair in Sakalis.

[31] Quoted in Bohdan Vedybida, ‘Parks of Socialist Realism Monuments: The Museum Management Aspect’, Scientific Bulletin of the National History Museum of Ukraine, 4 (2019), 675-693, 676.

[32] Yevheniia Moliar, ‘Rui_Nation. About the War with Sculptures and Monuments’, Your Art (Published: 29 May 2022, Last accessed: 1 July 2022, https://supportyourart.com/columns/ruj_nacziya/?fbclid=IwAR3jS_XGUw8UXgikZV98d5kr0UvkP7b2Hsj-Qj6zOLgj66DTIJbP6ALyaM8)